Some of the warm personal friends of Mr. Adams are taking unwearied pains to disparage the motives of those Federalists, who advocate the equal support of Gen. Pinckney, at the approaching election of President and Vice-President. They are exhibited under a variety of aspects equally derogatory. Sometimes they are versatile, factious spirits, who cannot be long satisfied with any chief, however meritorious:—Sometimes they are ambitious spirits, who can be contented with no man that will not submit to be governed by them:—Sometimes they are intriguing partisans of Great-Britain, who, devoted to the advancement of her views, are incensed against Mr. Adams for the independent impartiality of his conduct.

In addition to a full share of the obloquy vented against this description of persons collectively, peculiar accusations have been devised, to swell the catalogue of my demerits. Among these, the resentment of disappointed ambition, forms a prominent feature. It is pretended, that had the President, upon the demise of General Washington, appointed me Commander in Chief, he would have been, in my estimation, all that is wise, and good and great.

It is necessary, for the public cause, to repel these slanders; by stating the real views of the persons who are calumniated, and the reasons of their conduct.

In executing this task, with particular reference to myself, I ought to premise, that the ground upon which I stand, is different from that of most of those who are confounded with me as in pursuit of the same plan. While our object is common, our motives are variously dissimilar. A part, well affected to Mr. Adams, have no other wish than to take a double chance against Mr. Jefferson. Another part, feeling a diminution of confidence in him, still hope that the general tenor of his conduct will be essentially right. Few go as far in their objections as I do. Not denying to Mr. Adams patriotism and integrity, and even talents of a certain kind, I should be deficient in candor, were I to conceal the conviction, that he does not possess the talents adapted to the Administration of Government, and that there are great and intrinsic defects in his character, which unfit him for the office of Chief Magistrate.

To give a correct idea of the circumstances which have gradually produced this conviction, it may be useful to retrospect to an early period.

I was one of that numerous class who had conceived a high veneration for Mr. Adams, on account of the part he acted in the first stages of our revolution. My imagination had exalted him to a high eminence, as a man of patriotic, bold, profound, and comprehensive mind. But in the progress of the war, opinions were ascribed to him, which brought into question, with me, the solidity of his understanding. He was represented to be of the number of those who favored the enlistment of our troops annually, or for short periods, rather than for the term of the war; a blind and infatuated policy, directly contrary to the urgent recommendation of General Washington and which had nearly proved the ruin of our cause. He was also said to have advocated the project of appointing yearly a new Commander of the Army; a project which, in any service, is likely to be attended with more evils than benefits; but which, in ours, at the period in question, was chimerical, from the want of persons qualified to succeed, and pernicious, from the peculiar fitness of the officer first appointed, to strengthen, by personal influence, the too feeble cords which bound to the service, an ill-paid, ill-clothed, and undisciplined soldiery.

It is impossible for me to assert, at this distant day, that these suggestions were brought home to Mr. Adams in such a manner as to ascertain their genuineness; but I distinctly remember their existence, and my conclusion from them; which was, that, if true, they proved this gentleman to be infected with some visionary notions, and that he was far less able in the practice, than in the theory, of politics. I remember also, that they had the effect of inducing me to qualify the admiration which I had once entertained for him, and to reserve for opportunities of future scrutiny, a definitive opinion of the true standard of his character.

In this disposition I was, when just before the close of the war, I became a member of Congress.

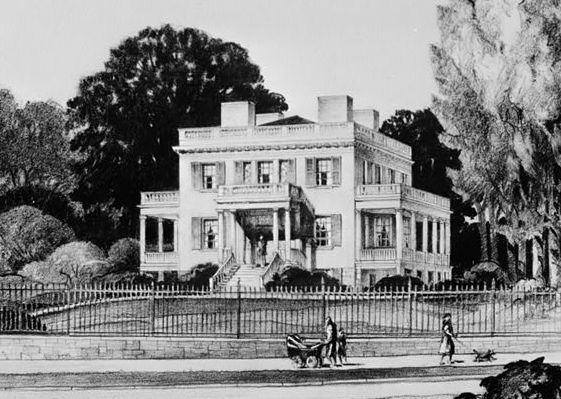

The situation in which I found myself there, was far from being inauspicious to a favorable estimate of Mr. Adams.

Upon my first going into Congress, I discovered symptoms of a party already formed, too well disposed to subject the interests of the United States to the management of France. Though I felt, in common with those who had participated in our Revolution, a lively sentiment of good will towards a power, whose co-operation, however it was and ought to have been dictated by its own interest, had been extremely useful to us, and had been afforded in a liberal and handsome manner; yet, tenacious of the real independence of our country, and dreading the preponderance of foreign influence, as the natural disease of popular government, I was struck with disgust at the appearance, in the very cradle of our Republic, of a party actuated by an undue complaisance to foreign power; and I resolved at once to resist this bias in our affairs: a resolution, which has been the chief cause of the persecution I have endured in the subsequent stages of my political life.

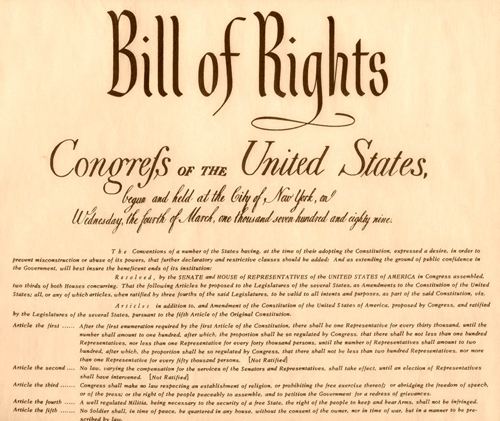

Among the fruits of the bias I have mentioned, were the celebrated instructions to our Commissioners, for treating of peace with Great-Britain;which, not only as to final measures, but also as to preliminary and intermediate negotiations, placed them in a state of dependence on the French ministry, humiliating to themselves, and unsafe for the interests of the country. This was the more exceptionable, as there was cause to suspect, that in regard to the two cardinal points of the fisheries and the navigation of the Mississippi, the policy of the cabinet of Versailles did not accord with the wishes of the United States.

The Commissioners, of whom Mr. Adams was one, had the fortitude to break through the fetters which were laid upon them by those instructions; and there is reason to believe, that by doing it, they both accelerated the peace with Great-Britain, and improved the terms, while they preserved our faith with France.

Yet a serious attempt was made to obtain from Congress a formal censure of their conduct. The attempt failed, and instead of censure, the praise was bestowed which was justly due to the accomplishment of a treaty advantageous to this country, beyond the most sanguine expectation. In this result, my efforts were heartily united.

The principal merit of the negotiation with Great-Britain, in some quarters, has been bestowed upon Mr. Adams; but it is certainly the right of Mr. Jay, who took a lead in the several steps of the transaction, no less honorable to his talents than to his firmness. The merit, nevertheless, of a full and decisive co-operation, is justly due to Mr. Adams.

It will readily be seen, that such a course of things was calculated to impress me with a disposition friendly to Mr. Adams. I certainly felt it, and gave him much of my consideration and esteem.

But this did not hinder me from making careful observations upon his several communications and endeavoring to derive from them an accurate idea of his talents and character. This scrutiny enhanced my esteem in the main for his moral qualifications but lessened my respect for his intellectual endowments. I then adopted an opinion, which all my subsequent experience has confirmed, that he is a man of an imagination sublimated and eccentric; propitious neither to the regular display of sound judgment, nor to steady perseverance in a systematic plan of conduct; and I began to perceive what has been since too manifest, that to this defect are added the unfortunate foibles of a vanity without bounds, and a jealousy capable of discoloring every object.

Strong evidence of some traits of this character, is to be found in a Journal of Mr. Adams, which was sent by the then Secretary of Foreign Affair to Congress. The reading of this Journal, extremely embarrassed his friends, especially the delegates of Massachusetts; who, more than once, interrupted it, and at last, succeeded in putting a stop to it, on the suggestion that it bore the marks of a private and confidential paper, which, by some mistake, had gotten into its present situation, and never could have been designed as a public document for the inspection of Congress. The good humor of that body yielded to the suggestion…

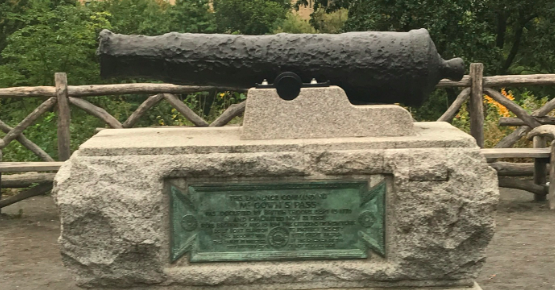

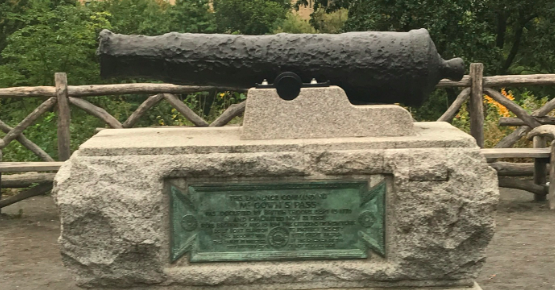

While exploring the Revolutionary War/War of 1812 forts on the Secret Places of Central Park tour you’ll come upon a fortification which includes a genuine British cannon from the Revolutionary War. Salvaged from the H.M.S. Hussar after shipwrecking off the East River in 1780, it was eventually donated to Central Park. After being put into storage for a number of years, the Central Park Conservancy, in their plans to restore the Revolutionary War/War of 1812 fortifications, planned to put the artillery piece back on display. While restoring it in 2013, they found a cannonball, wadding, and frighteningly enough, over a pound of gunpowder, making this, in theory, a still-loaded cannon since 1780. The Bomb Squad were called to remove the explosive material, and eventually, it was put back on display for you to see!

While exploring the Revolutionary War/War of 1812 forts on the Secret Places of Central Park tour you’ll come upon a fortification which includes a genuine British cannon from the Revolutionary War. Salvaged from the H.M.S. Hussar after shipwrecking off the East River in 1780, it was eventually donated to Central Park. After being put into storage for a number of years, the Central Park Conservancy, in their plans to restore the Revolutionary War/War of 1812 fortifications, planned to put the artillery piece back on display. While restoring it in 2013, they found a cannonball, wadding, and frighteningly enough, over a pound of gunpowder, making this, in theory, a still-loaded cannon since 1780. The Bomb Squad were called to remove the explosive material, and eventually, it was put back on display for you to see!