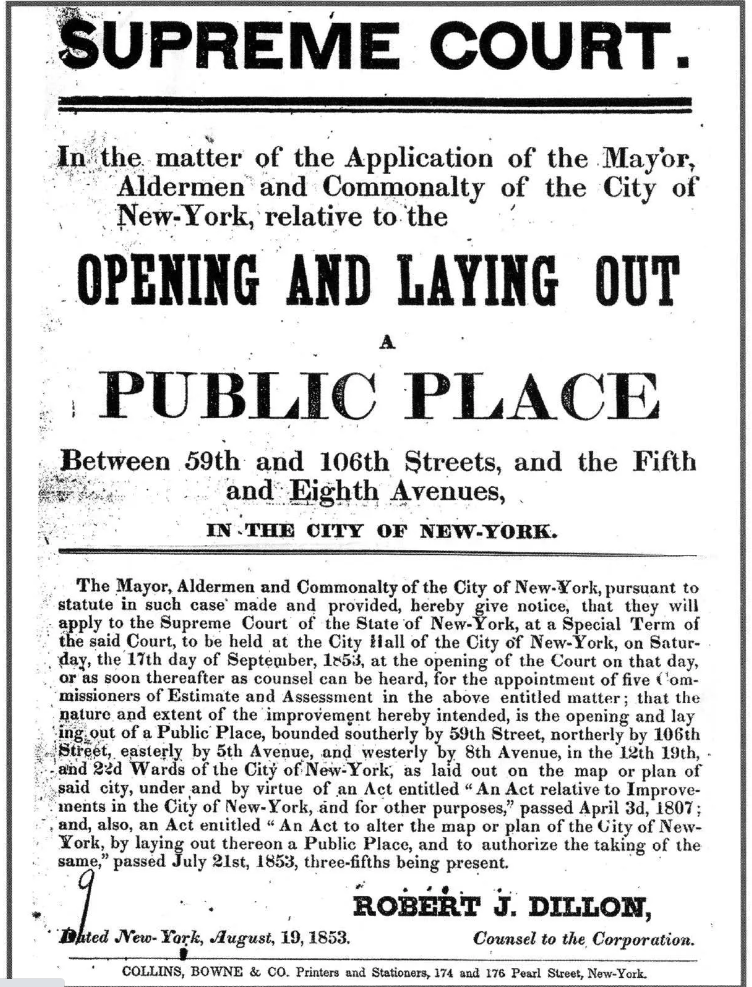

Discover Central Park’s hidden northern wonders — from the wild North Woods and tranquil Pool to the elegant Conservatory Garden and scenic Harlem Meer. Join Revolutionary Tours NYC for the Secret Places of Central Park Tour and uncover the park’s most peaceful and historic corners.

The Secret North: Hidden Beauty in Central Park’s Quietest Corners

Most visitors to Central Park never make it north of 100th Street. Yet some of the park’s most enchanting, mystical, and least-visited landscapes lie beyond it — places where the city seems to melt away, and Olmsted and Vaux’s grand design reveals its most intimate secrets. On our Secret Places of Central Park Tour, we explore these northern gems, where history, artistry, and nature intertwine in surprising ways.

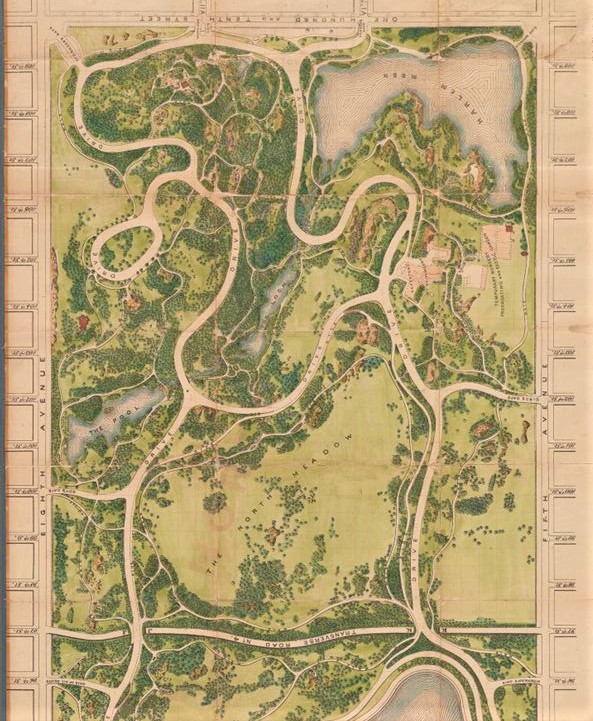

The North Woods – New York’s Wilderness

The North Woods feels like a wilderness transported to Manhattan. Designed to evoke the Adirondacks, it’s a landscape of towering oaks, rustic bridges, and a tumbling stream known as the Loch, winding its way toward Harlem Meer. During the park’s construction between 1858 and 1873, nearly 20,000 workers, many of them Irish and German immigrants, reshaped this rugged terrain by hand. They blasted through bedrock, diverted water through dozens of miles of underground pipes, and planted thousands of trees to create this illusion of natural wilderness. Today, the North Woods remains one of the most peaceful refuges in the entire city — a place where you can hear woodpeckers instead of traffic and follow winding trails that reward the curious wanderer.

The Pool – A Serene Hidden Mirror

Just west of the Woods lies the Pool, a tranquil body of water at 100th Street and Central Park West. It’s one of the park’s loveliest and most overlooked features, surrounded by willows and red maples that reflect perfectly in the water’s surface. In spring and fall, migratory birds rest here, while in winter, the scene turns into a snow-dusted tableau worthy of a painting. The Pool captures Olmsted and Vaux’s genius for designing spaces that look entirely natural yet were painstakingly crafted to offer changing beauty with each season.

The Conservatory Garden – A Formal Oasis

A few blocks east at Fifth Avenue and 105th Street stands the Conservatory Garden, a masterpiece of horticultural artistry hidden behind the ornate Fifth Avenue Vanderbilt Gate. Divided into three distinct styles — Italian, French, and English — this six-acre garden bursts with color and structure from the spring through the fall. It’s one of the park’s quietest corners, missed by even seasoned New Yorkers. Whether it’s the symmetry of the Italian terrace or the romantic Secret Garden of the English area, every section reveals another layer of Central Park’s personality — cultivated, elegant, and serene.

Harlem Meer – The Park’s Northern Lake

At the park’s northeast edge lies Harlem Meer, a shimmering lake bordered by elms and willows and framed by a view of Harlem’s skyline. The word Meer means “lake” in Dutch, a nod to the area’s early colonial history. In Olmsted and Vaux’s design, the Meer served as both a picturesque water feature and a recreational gathering place. Today, it remains one of the park’s most tranquil settings — perfect for birdwatching, or simply standing by the shore as the light ripples across the water. The Meer represents the ideal balance between nature and city — the kind of harmony Central Park was built to create.

Discover the North with Us

These northern landscapes and other areas of the areas of the northern park tell a quieter story of Central Park — one of tranquility, mystery, and discovery. On our Secret Places of Central Park Tour, you’ll explore these hidden sanctuaries, uncover the history behind their design, and experience a side of the park most visitors never see.

Best Central Park Walking Tour in New York City